I actually enjoyed reading this, you might too:

Author: DavidWebster

Is Mind-Body-Spirit (MBS) Spirituality Necessarily Individualistic?

Thanks to Lloyd for this material:

Our colleague Dave Webster’s latest book Dispirited (Winchester/Washington: Zero Books, 2012) argues, among other things, that the form of spirituality promoted by MBS advocates tends to be individualistic and fosters disengagement from the socio-political sphere. Webster is in good company as this is also argued by, amongst others, Robert N. Bellah, Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler & Steven M. Tipton, Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985); Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991); Charles Taylor, Varieties of Religion Today (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002); and Adam Possamai, Religion and Popular Culture: A Hyper-Real Testament (Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2007). However, within the sociology of religion, this remains a contested area with a number of sociologists arguing for “engaged spirituality” rather than the “spiritual individualism” advocated by the above scholars. A…

View original post 370 more words

on mindfulness, muggles, & crying wolf

An important debate – one we’ll be seeing more of as mindfulness spreads more and more.. I foolishly read the comments too..

This month has been bubbling with various posts on Eastern scholars decrying Western Mindfulness. It began with Ron Purser and David Loy’s HuffPo article, Beyond McMindfulness which is likely the first time anyone from the Buddhist scholarship community has overtly taken on the therapeutic, coaching Mindfulness machine. In brief, Purser & Loy expressed concerns that the current movement of Mindfulness is not only denaturing the dharma but also lending power to corporations so that already-beleaguered employees can be lulled into a somnolent state through practices like “nonjudgmental awareness.”

The results of the Purser & Loy article were not what I would have expected: linguistic mudslinging. Protests from what may be called the “secular” mindfulness groups were no less than defensive and somewhat histrionic. Sadly, there were worthy points in the protests but mostly lost in the defensiveness and the mutually admiring comments that followed. (There’s…

View original post 1,262 more words

Podcasts and Reviews..

A bit quiet over the summer, but a recent podcast I did with Stephen Schettini (AKA The Naked Monk) has come out. We talk about the book, and various things. One of the most interesting is the idea of what would have happened to the traditional forms of religion in Western Europe and the US if Buddhism hadn’t had such a draw on many dissatisfied but enthusiastic people over the last 4 decades or so: You can hear the podcast at http://www.thenakedmonk.com/2013/07/26/2-david-webster/.

On the same day, a review of Dispirited came out on the LSE Books website. The review is HERE. Although the reviewer doesn’t agree with everything, she offers a really engaged and critical review that I thought was rather good. She has me pegged as a neo-Kantian, which I am not totally happy about (though arch Buddhist-Kantian Justin Whitaker will be pleased). However, she can only have got that impression from the book – so it’s probably my fault.

Furthermore, the reviewer is correct to point out that it’s an unfinished account: the neither-religious-nor-spiritual response is still in need

of better, more philosophically developed, versions which I only hint at in the book…

Squeezing into Uncomfortable Spaces: Scholarly Objectivity and Strong Opinions.

Below is a version of the paper I gave at CESNUR13. Clearly I will have said more in person: digressed, embellished and clarified, no doubt. But though it may be of some interest…

—

Isn’t the University emblematic of free speech? It is where we say what can’t be uttered in commercial contexts, or in faith contexts where certain claims are sacrosanct. Shouldn’t the University be where we blaspheme?

For this paper, you’ll have to forgive me the self-indulgence of speaking about my experience and myself. It’s a subjective-experience-based paper, and that seems to require a faintly autobiographical introduction. I outlined the paper to colleague who said: “So it’s all about you then? Why don’t you go and do some proper scholarly work instead?” Charming. But actually I want to begin with some

personal accounts that I think lead to general considerations that impact on the way religions are studied, evaluated and discussed in scholarly contexts. We’ll see…

Back in September 2010, back when we were all young and fabulous, I found myself in Turin, at something called ‘CESNUR’. Given that my research interests are mostly to do with the philosophical implications of ideas in early Pali Buddhist texts, a number of people (sometimes including myself) wondered what I was doing there. Some of them asked me.

In response I tried to vocalise an interest I had in New-Age / Mind-Body-Spirit thought, and why I had such strong opinions about it. As often happens, being forced to talk about this helped me crystallise my thoughts, and in conversation I began to formulate the reasons that underpinned my response.

I went home, got busy, and slowly let the ideas simmer. Then I sent off a proposal and in Summer 2011 sat in cafés in Cheltenham and wrote a short manuscript. The resulting book: Dispirited: How Contemporary Spirituality Makes us Stupid, Selfish & Unhappy was published in June 2012.

This was a personal statement of (dis)belief that also engaged with, and represented, my experience as a student of religious traditions, particularly new-age ones. It was provocative and personal, but I felt it also made a set of (mostly) reasonable arguments. What I had, from some quarters, was an extreme reaction. I University lecturers asked questions in raised voices, others tut-ed non-stop as I gave papers on the book, some wrote to me insisting that I should not be allowed near young minds. I felt myself pushed into an uncomfortable academic space that this paper explores.

So what was it that was so annoying to people? Well, the book isn’t descriptive. I don’t quantify, offer data, or draw summaries based on qualitative surveys. My evaluation isn’t limited to what I think best sums up the practices or beliefs or certain groups. I go a stage beyond this and offer an explicit ethical evaluation. I argue that certain ways of holding ‘spiritual’ beliefs is a bad thing. That there are a particular class of attitudes and stances, most commonly those associated with the slogan ‘Spiritual But Not Religious’ (SBNR) that are toxic and dangerous. You can perhaps begin to se why some didn’t like it. I didn’t expect those it criticised to much like it – I expecting the kicking I got on SBNR blogs, and was happy to shrug it off. However, a lot of academics seemed uncomfortable with the book. While talking about problems with the SBNR, I also develop a strand of outspoken atheism in the book, where I commend the abandonment of all spiritual and religious belief in favour of a reckoning with an apparently bleak nihilism. The reception I received (not entirely positive) from Religious Studies circles led me to ponder the mechanics of claims about appropriate speech in these settings.

Scholars of religious traditions are expected, on one hand, to maintain a stately indifference to the object of study. To describe, note, remark and critically assess: an engaged and engaging task, but one where they leave their own personal commitments at the door. Most of the papers we’ve been hearing here have been evaluative, critical and reflective -rather than merely descriptive- but the critique is mostly of the methods applied, and whether they indicate x or y, and how we might read and make sense of data gathered. We, as a group of scholars (is there a collective noun for RS scholars? We certainly talk of a confusion of philosophers, and I’ve heard reference to a malice of historians.. anyway..) are reluctant to offer certain kinds of judgement- at least in part. I’ll return to this with reference to the area of Theology shortly.

On the other hand, scholars of religion are eminently qualified to say what they assess to be helpful or harmful in varied traditions – to speak from a standpoint of both knowledge and from deep personal commitment to a position. Theologians have, indeed, often done so. One might go further and argue that the critical evaluation that makes the study of religion more than just a mere process of cataloguing and describing requires some form of judgment as to the social, political and ethical impacts of those phenomena studied. Achieving this, while not falling prey to accusations of being partial, an advocate instead of a scholar, can push one into a challenging space. One might even argue that either one is an advocate OR a scholar. That one cannot be both seems to help us perpetuate some pseudo-science myth of actual objectivity. But we are not scientists. Some may be so more than other, but many of us are philosophers, and interested in ethics. This is not a study of an entirely objective nature. But it does not mean well-informed judgements are not possible: we really are all both – I have views, judgements, these come from the academic and the personal – but to say the former is objective and the latter subjective is rather naive.

Let me put this another way – do we find scholars in our area advocating belief or disbelief in specific traditions, or at least offering up their benefits or disbenefits? This depends on the context of course. In my classroom, I mostly resist inflicting my take on my students: although where there are positive aspects, especially where they might have missed them, I may mention them. They may have a variety of negative misconceptions about the impact of various faiths, often derived from the media, that need addressing. I may talk about social justice movements in South American Christianity, or Islam’s intellectual and scientific influence via Cordoba, or Buddhist fundamentalists – correctives to populist simplifications. But clearly I won’t have classes on “why Religion X is wrong” for example – although in a controversial area like Cults & Sects, I wouldn’t be surprised to see some focus on claims of mis-deeds – but NRM studies is probably (due to initial claims of NRM harm / brainwashing) more mature than many areas at handling this: is this true?

But outside the classroom? Let’s look at this – my colleagues in Theology write books which take the ultimately benign nature of a Theistic God’s plan for us as a given. They stand (some of them) in pulpits, write devotional articles and write books defending belief (The Twilight of Atheism, one of the most scrappy pieces of apologetics ever written, for example). Apologetics seems almost an acceptable academic undertaking. Yet it is primarily a form of value-derived, conclusion-led, biased, partial and partisan activities one can engage in. It often has fixed conclusions which are not up for debate- only for defence. Either apologetics is, without question, not scholarship of any shade whatsoever, or we need to admit that one can construct arguments where the advantages and disadvantages of the impacts of positions is open to question. Compared to apologetics, this seems a very moderate undertaking indeed.

I think part of the suspicion I encountered was related to a general, I think, curiosity. Why would someone with not only no religious commitment but an active hostility to non-religious spirituality (actually it was incredulity, not hostility, but let’s not quibble) work in religious studies? Well, I often wonder the same thing. But: I know why: because I’m interested in how we, as a species, have sought to come to terms with various existential realities. Religion is, amongst other things, in large part, that story.

Another aspect that I merely suspect, is that what is more acceptable for books by RS scholars are either that they are descriptive (often critical descriptive, I’m not disrespecting them), or they are positive. About what religion (in general or a specific tradition) can offer people, what problems it can solve, how it can contribute to social or cultural life, rather than claiming explicitly negative outcomes.

Back in the classroom.

Of course, the approach to the teaching and engaging with the study of religion sometime known as ‘phenomenological’ (a term I’d avoid myself, reserving it for its much more useful deployment within philosophy), encourages us to leave value-judgements aside and park our commitments. There are two, related, reasons why I think this is objectionable nonsense.

1: Our commitments in respect of faith are related to our study. That I could disentangle what I believe from examining what I do and don’t believe, seems perverse. Features of traditions incline towards or away from them and towards them. I learn more of these when I study. Sure, I observe critical accountability when I teach (nice phrase, I stole it from a Biblical scholar) – but I would be less of a teacher if I didn’t engage with the traditions as I find them.

<e.g. In my class – I may say ‘I am troubled by the tendency of this tradition to xx, do you think I’m being fair to it?’,or ‘isn’t this theory of social justice compelling and preferable to theory z? Or maybe not- tell me why I’m wrong’. Clearly there are issues of authority and expertise.. I’d do this less early in the degree, when they still have some respect for me and less subject- knowledge, confidence, etc, and more as they become more autonomous and opinionated.. >

2: It’s impossible and dishonest to pretend this phenomenological approach is possible (and see reason 1- it’s not even desirable anyway). We do have opinions here, let’s not pretend we don’t. We can tell students that we won’t yet be revealing them – but to style ourselves as scholar-robots is to forget the lesson Nietzsche teaches in Beyond Good and Evil’s opening chapter:

What makes one regard philosophers half mistrustfully and half mockingly is not that one again and again detects how innocent they are – how often and how easily they fall into error and go astray, in short their childishness and child likeness – but that they display altogether insufficient honesty, while making a mighty and virtuous noise as soon as the problem of truthfulness is even remotely touched on. They pose as having discovered and attained their real opinions through the self evolution of a cold, pure, divinely unperturbed dialectic… while what happens at bottom is that a prejudice, a notion, an ‘inspiration’, generally a desire of the heart sifted and made abstract, is defended by them with reasons sought after the event – they are one and all advocates who do not want to be regarded as such, and for the most part no better than cunning pleaders for their prejudices, which they baptise ‘truths’

We need to actually be more phenomenological in the philosophical sense, not the Religious Studies sense: we encounter religions as actual beings, with a temporal trajectory towards the grave, with a place on it, with commitments and beliefs. Yes, let’s be fair, allow for learning and for a multiplicity of voices, but let’s not treat readers of our work like babies, and pretend that one of the voices in this multitude of things said is not our own.

Self Designation: Spiritual? Religious? Neo-Religious? Åndelig?

At the CESNUR 2013, I ask Knut Melvaer and Margrethe Løøve about their work…

Happiness and The Welfare of Others

I recently talked to Cheltenham Sceptics in the Pub – which was a great evening, with some livelydiscussion.

Now, I’ve blogged about happiness before – but I had some thoughts as a result of this talk… One of the great concerns I’ve had about all this movement for ‘Happiness’ is that it seems to evade the issue of whether we deserve to be happy – about the primary connection between Virtue and Happiness. If we stop caring about others – just pleasing ourselves – we can be quite cheery can’t we? The example I use in the book is the guy at the end of the Woody Allen movie Crimes and Misdemeanours – he seems content, happy and to have got over his murderous acts by forgetting about them..

I was looking again at the Action for Happiness web-site again – and spotted something interesting. There is a real focus on addressing this very critique. That seems like a good thing.. Look:

Creating a happier society for everyone. That sounds much more like it, doesn’t it?

Sure. Why not?

But what does this happiness consist of? Being less rude to other drivers? Giving biscuits to my students? Working to alleviate material poverty and establish a more equitable society? I clicked the ‘Read More’ link. I then read this:

Members of the movement make a simple pledge: to try to create more happiness in the world around them through the way they approach their lives. We provide practical ideas to enable people to take action in different areas of their lives – at home, at work or in the community. We hope many of our members will form local groups to take action together.

We have no religious, political or commercial affiliations and welcome people of all faiths (or none) and all parts of society. We were founded in 2010 by three influential figures who are passionate about creating a happier society: Richard Layard, Geoff Mulgan and Anthony Seldon.

What lept out at me here was the section that said ‘We have no religious, political or commercial affiliations‘. Does that mean Action for Happiness has no political position? If we are going to spread happiness by more than charity donation, by holding open doors and being less of a curmudgeon – being overtly political, alleviating income and health inequality, establishing less Patriarchal relations between genders, fighting racism and ending privilege seem quite important too. There is some thing oddly apolitical about the claims of the Happiness Movement, faintly neo-liberal or post-ideological too.

At their guidance, there are some claims about neuroscience that I’m not qualified to judge (“Altruistic behaviour releases endorphins in the brain and boosts happiness for us as well as the people we help.”), but these ways of helping – while undoubtedly noble and virtuous – seem like rather thin responses to a world riven by material poverty. Shouldn’t I not only show my care for others by, as well as volunteering, helping my neighbours and the things in the poster below, also getting my hands dirty in the real work of happiness: and that work is called politics.

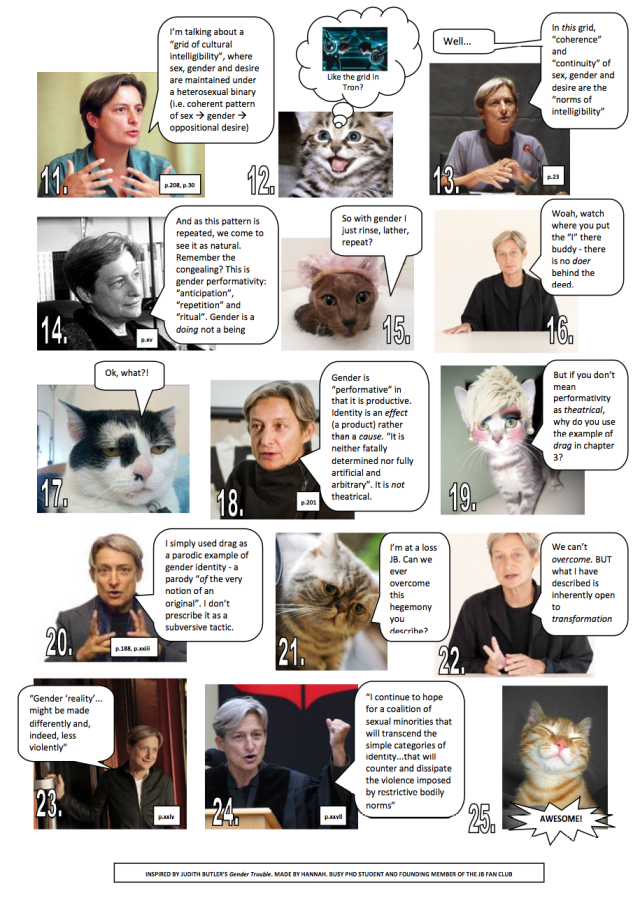

Judith Butler Explained with Cats

A bit off topic – but hard to resist..

Following hot on the heels of Foucault Explained with Hipsters, here’s JB’s Gender Trouble explained in Socratic dialogue style. With cats.

All page references from Butler, J. (1990 [2008: 1999]). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York; London: Routledge.

Got any more ideas for philosophy/sociology/gender theory you’d like to see explained in comic form? Let me know in the comments below.

Militant Atheists and associated nonsense..

I see TED has stepped away from the Rupert Sheldrake talk at one if its TedX events.. Then Deepak Chopra and various folk object, etc –  and we finally have a response HERE, that defends TED. I am not a great Fan of TED talks really, but they seem on the ball here. Whatever you think of Sheldrake’s interventions in Philosophy of Science (and I don’t think much of them, but that’s another matter), the claims he does make for actual phenomena don’t seem at all well supported..

and we finally have a response HERE, that defends TED. I am not a great Fan of TED talks really, but they seem on the ball here. Whatever you think of Sheldrake’s interventions in Philosophy of Science (and I don’t think much of them, but that’s another matter), the claims he does make for actual phenomena don’t seem at all well supported..

However, as the comments at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/chris-anderson/ted-censorship-consciousn_b_3115145.html show, this is a bunfight where everyone seems to argue from set positions, and little on no progress is made. So I think I’ll stay out of it..

However, I just wanted to note another thing that seems widespread, but which is also very annoying. The term ‘Militant Atheist‘. The term is everywhere and seems misleading. I suspect it is often intentionally so.

Sure – many new atheists may be assertive and combative. Some are idiots. Richard Dawkins seemed to have been guilty of misogyny and there seems to be worrying Islamophobic tendencies in some New Atheist circles. I talk about some of my concerns with how contemporary atheism characterises religion in the book:

Since Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion, it seems like the talk in the virtual and fleshy public spheres has been

dominated by an interaction by two ever more shouty choruses. Gathered on one side, we have the serried ranks of atheists and their long-standing sub-corp of the collectively minded known as humanists. Across a chasm of mutual, wilful misapprehension from them are gathered the (largely Christian) hosts of Theism’s defenders. I want to suggest here that this debate has become ever more futile, distracting and shrill. Given the largely nihilistic tone of my existential world view, one might expect me to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with Dawkins, Dennett, et al – and I have felt that draw. However the polarising, simplifying nature of the arguments rehearsed leaves, I believe, a substantive middle ground untouched. Further, both sides are ever-more prone to treating religious faith merely as a matter of correspondence-theory metaphysics. Colleagues will know, and readers can surmise in safety, that I am not the world’s greatest fan of Theology – but it’s as if the discipline has never existed. You’d never know that reflective, intelligent, humane and critical people had actually given the nature and content of religion some sustained and rigorous inspection already.

Many theists and atheists seem to have got rather caught up on a propositional account of religion – which I’ve spoken about elsewhere at

length, so much so that some aren’t even sure about the term atheist, and others think it needs a ‘+’. Fine – we can argue about how well or badly various atheist accounts fully engage with various religious traditions, thinkers ideas…

Ok – but I wanted to pause here and think of the use of this term ‘Militant Atheist’. Of course , there have been past instances of Atheists standing violently against religion – though in some cases it’s arguable how much their atheism, rather than their being totalitarian despots, or statist communists, or whatever it is, drove their violence and crimes. And yes – we need to recall that in the cases of religious violence too: people may have complex and mixed motives. But…. Despite all this, it is dishonest to style the current wave of blog-writing, argumentative, book-publishing, seminar-holding, bus-sign displaying atheists as ‘miltant’.

When we talk of miltant Christians or Muslims, or Buddhists, whether we are wholly correct in our details, we are referring to people who carry out acts of violence in the name of their alleged-faith-commitments. Do atheists call for the closure of churches, by force? Do they call for religions to be outlawed? For violence against places of worship? While we may find an example on the web (isn’t that true of everything?) – generally they just don’t.

Many ‘new’ atheists may be misogynistic, or Islamophobic, or muddle-headed, or overly sarcastic, or bombastic. Some are respectful and subtle, and wise. But, taken in the round, they are not militant. To talk about Militant Atheists as if we mean, in this context, by ‘militant’ the same thing as we mean by ‘militant’ when we say ‘Militant Christian’ (for example) is just misleading…